21. July 2021

Sehen Sie sich das KOSTENLOSE On-Demand-Webinar von Reuters mit dem Titel „Addressing the Battery Module Challenges“ (Bewältigung der Herausforderungen bei Batteriemodulen) an. Darin erörtern wir das komplexe Thema der Elektrofahrzeug-Batteriemodule und der Montage von Autobatteriesystemen. Sehen Sie sich dieses kostenlose Webinar an und erfahren Sie, warum viele Batterieprojekte scheitern, wohin sich der Markt für Elektrofahrzeugbatterien entwickelt und warum es für Ihren zukünftigen Erfolg entscheidend ist, jetzt Ihren Partner zu wählen.

In diesem Gespräch gehen wir auf Folgendes ein:

- Wie Unternehmen innerhalb weniger Monate eine Qualitätsbatterie herstellen können, von der Zelle über das Modul bis zum Batteriepack.

- Wie die Umsetzung kontinuierlicher Prozessoptimierungen mithilfe von Datenüberwachung und Analytik die Qualitätskontrolle und den Durchsatz verbessert.

- Die Beziehung zwischen Erstausrüster, Lieferant und Hersteller als entscheidendes Element für den Erfolg.

Schauen Sie sich jetzt das Webinar „Bewältigung der Herausforderungen bei Batteriemodulen“ an

HINWEIS: Das Video ist auf Englisch

Referenten

Gastgeberin

Brenda Staines

Senior Project Director, Reuters Events.

Moderator

Jim Motavalli

Freiberuflicher Autor im Automobilbereich.

Diskussionsteilnehmer

Udo Panenka

President, ATS Industrial Automation.

Diskussionsteilnehmer

Martin Starkey

Managing Director, Ricardo’s Performance Global Division.

Diskussionsteilnehmer

Robert Lane

Gründer von Manaflex.

Transkript

Brenda Staines

Go ahead Jim.

Jim Motavalli

Yes, I’m the author of two books on the electric vehicle. The space is now evolving so rapidly that we must keep very close tabs on it and how we’re moving ahead. I think that we have a very exciting panel here. We have Udo Panenka, who’s president of ATS Industrial Automation, Robert Lane, the founder of Manaflex, and Martin Starkey, who’s the managing director of Ricardo Performance, global division.

What we’re looking at in this panel is a situation where the EV market is growing very rapidly internationally; there were maybe 3 million electric vehicles sold in 2020. But we’re talking about as many as 12 million by 2025, and maybe 31 million in 2030.

And the questions are, do we have the capacity? Will we be able to meet the challenge of providing batteries for all those cars, battery packs, and modules for the incredible demand? Every day there’s a new announcement of electric vehicle launches, and all the automakers are talking about no longer producing internal combustion.

We just heard that the European Union is talking about banning all gas and diesel vehicles by 2035. That’s very dramatic. There were already such laws on the books in various States in the US and in European countries and Asia, indeed all over the world. So, are we going to be ready? Let’s just have introductions from each of our speakers. Udo, do you want to start?

Udo Panenka

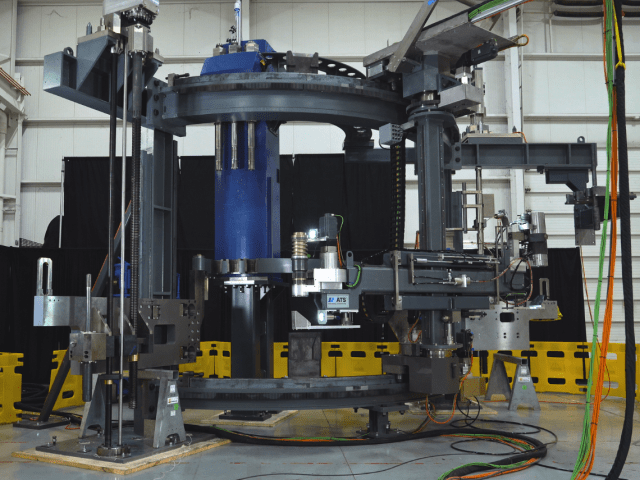

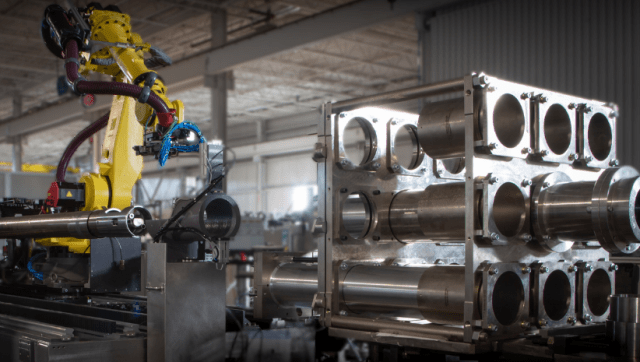

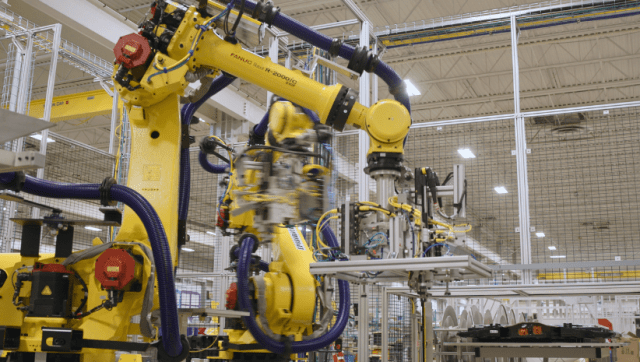

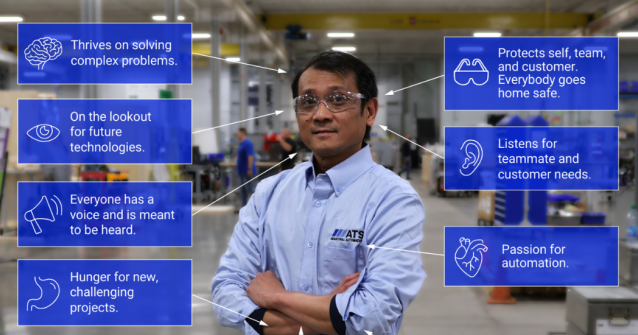

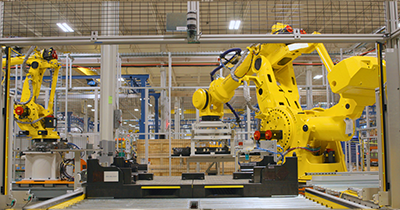

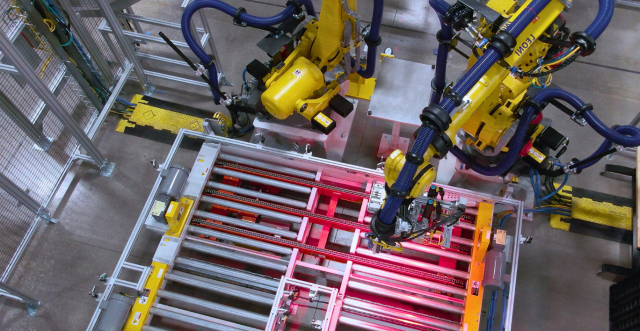

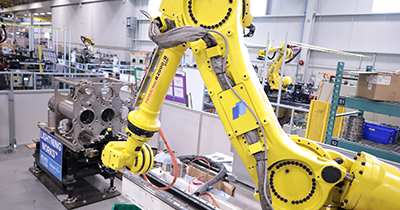

Absolutely, I believe we will not be ready. But let’s start with the introduction. My name is Udo Panenka. I’m the president of ATS Industrial Automation part of the ATS Group, which is one of the largest global automation players with more than 5,000 associates.

At ATS Industrial Automation, eMobility is a key strategic market. And when we talk about eMobility, it’s mainly battery assembly and fuel cell assembly and testing for both. We have delivered more than 70 projects in this space over the last 20 years. I’ve been working for the last 13 plus years for companies with a strong lean focus and I’ve been looking at how the auto industry is driving the transformation towards greener transportation. I can see an incredible amount of what we call in lean muda or waste here within this entire process. So, I have a dramatic passion for working together with our partners, our OEMs and their suppliers, and really finding vendors and disruptive ways to help facilitate this transformation. Thank you, Jim.

Jim Motavalli

The idea that there will not be enough battery capacity is very dramatic, and we’re going to focus on that in the panel. It’s something that we must address and must be ready for if we’re going to actually make this transition to all electric vehicles. Robert Lane, can you tell us about you and your perspective? You’re out there in Hawaii, right?

Robert Lane

Yes. Over on the Big Island. I started my career at Lockheed Martin. But I now focus on weather satellites and related environmental technologies. I realized that making a big change needed to be focused on materials and on solar, battery, those types of technologies. So, I started getting into solar and worked on solar arrays and then got into battery technologies, where I went into Tesla right after IPO and worked there for seven years on different projects including the Model S and then Model 3 and eventually led the Tesla energy design for Powerwall 2. So, I have a fair bit of experience working in batteries from early days and decided there’s a lot of big holes in the ability to make batteries at scale, including interconnecting components. I started my own company called Manaflex and partnered up with some suppliers and some engineers and we decided to just go for it.

Jim Motavalli

Yes, Martin, I should have mentioned that Tesla’s solution is to build its own battery factories. They are only basic and not building cells, but doing packs and modules and similar work, and they are still dependent on suppliers for battery cells. Martin Starkey tell us about you.

Martin Starkey

Yes. Thanks, Jim. So as Jim mentioned, I’m the managing director of Ricardo Performance Products, Ricardo is a well-known and well-respected engineering and manufacturing firm, with over 100 years in developing solutions in automated powertrain technology. Obviously, for most of that time the focus was on combustion engines and multi speed transmissions while more recently the focus has evolved into a very different offering around supporting the electrification journey. So, the products that we produced once upon a time, the fire breathing V8’s for sports cars and eight speed DCTs are past and we are now looking at how a dense battery system and how super-efficient, super lightweight, single speed e-axles move us forward. Amongst our great portfolio products, we’re doing things like Formula-E, with the world cup championship team using a product from us.

So, it is a really exciting journey that we’re on, and we’re looking at how we help make Udo’s prediction at least slightly wrong, that some of that capacity is there, especially in the niche volume area. Thanks, Jim and thanks for the introduction.

Jim Motavalli

Great. I’m just going to remind people who are watching this at home that you can ask questions by clicking on the Q&A button, and we’ll look at those going forward. I will ask questions of our specific panelists, but others will be able to chime in on the question.

The overarching question is: what are some of the challenges of EV battery production capacity and being able to meet all the announcements that have been made?

Let’s start with Udo.

Udo Panenka

Yes, from my perspective that’s the elephant in the room. If I step back, I think there is on the one hand what I call ‘the magic triangle.’ And then on the other hand there are underlying issues.

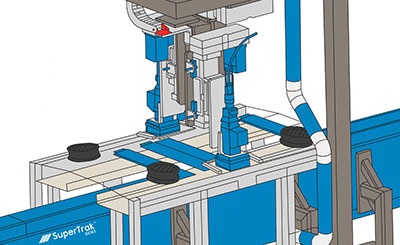

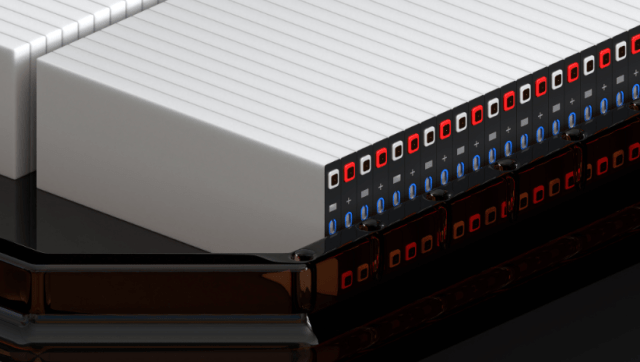

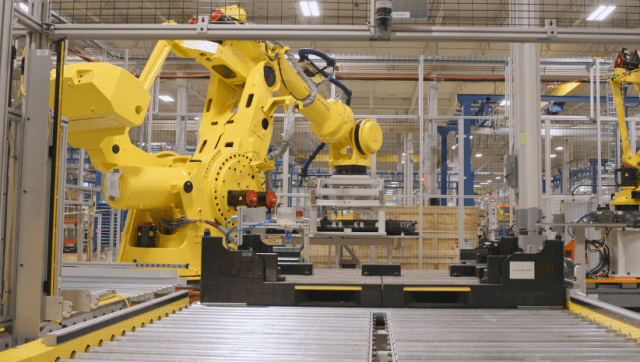

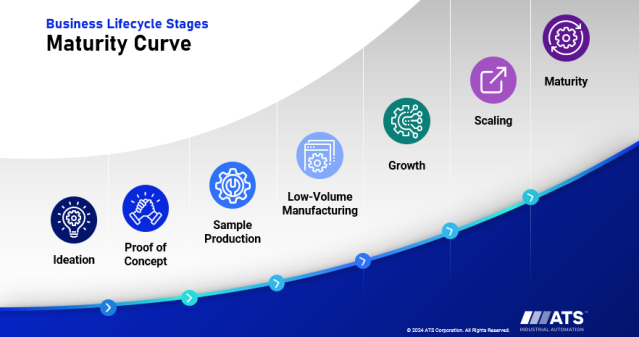

To me the magic triangle is that battery technology that is improving at a dramatically rapid pace. We don’t yet have stable products, and much is still evolving that affects the car’s range and charging that impacts battery cost. The battery is not stable but rapidly evolving and costs continue to drop yearly in the 10 plus percent range. At the same time, when I look at many of the automation projects in the industry, such as building a battery assembly line, a model and pack assembly line, they take between two and three years from the RFP, request for proposal, to the full production ramp up.

On the other hand, the other piece is automated assembly lines, how they’re designed today, the way they are written today. Basically, these lines cannot be easily and flexibly adjusted to new battery designs. If you take these three factors together, unstable battery design, evolving costs and lack of adjustability, this has been called ‘a setup for failure,’ and we believe this to be behind why many of today’s projects are not working as well as they should be.

Jim Motavalli

What you are saying is rather alarming and you are delivering a wakeup call to the industry. Robert, do you want to comment on that? Do you have thoughts on whether we’re approaching or going over a cliff here with battery delivery?

Robert Lane

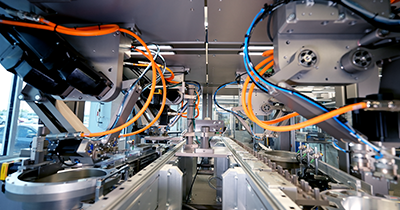

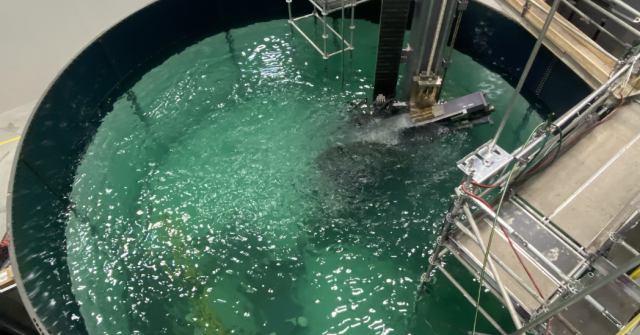

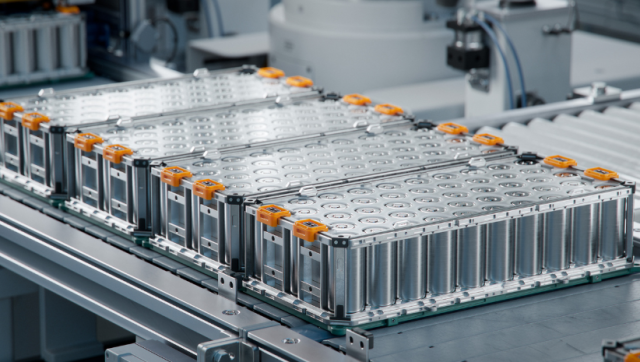

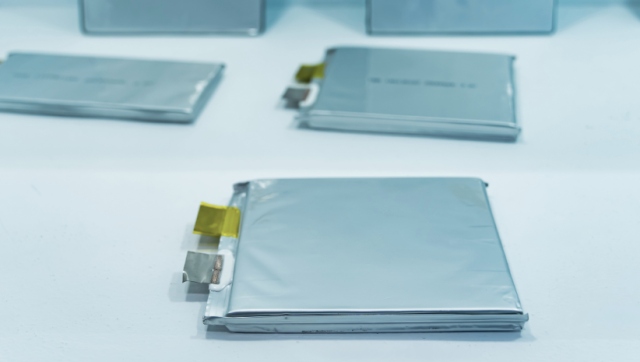

Certainly. I think we have gone over a cliff locally because of COVID-19. The cell shortage is quite difficult to deal with, but I do think that we are going to catch up very fast because there’s a lot of attention on this. When you have a battery, you have 1,000’s of cells, whether it’s cylindrical battery, prismatic battery, or pouch battery, and dealing with those cells is complicated. There are very high-precision tolerances for placing and interconnecting the cells. That’s a challenge that you see every day and it’s just one of those things where you need to really be cognizant of addressing every single design choice very carefully and keeping it simple. We must think about the battery up front.

It’s very important that reliability is thought of because it’s not like we have one cell go out, but instead it’s one over the entire number of cells in the battery and so is multiplied by the number of in-series bricks. So, when you reach that full capacity in a brick, it’s going to limit that brick, giving you a percentage upwards of one, two. And as the cells get bigger with less parallel cell counts, the percentages increase in terms of your capacity fade if you don’t do that cell interconnect correctly. So there’s a lot of attention right now on how to interconnect the cell ultra-reliably and ultra-fast, and so you want to choose equipment that’s just really good quality and people who know what they’re doing because they’ve been doing it for a while and have proven track record. We want to couple that with highly compelling new technologies to enable this market.

Jim Motavalli

Martin, do you want to get in on that? Just looking at that big picture question. Are we facing a supply problem?

Martin Starkey

I think we are Jim and I was just going to step back a little bit. Strategically, I think one of the large challenges here, if we look where battery technology came from, things like laptops as huge consumers of battery cells. That was a product that had a relatively short life and with the next generation laptop you could introduce a new cell relatively easily; it was a rapid turning market.

If we look at automotive it’s a very different mature market and is systems driven for all the right reasons, those being that they want to bring a quality assured, well developed product to market because the consumers demand it; that is an expensive investment. And, you’re trying to mesh it into an equally massive industry that’s been all around innovation and new products constantly coming to market in terms of the battery cells themselves.

To just give you one interesting challenge that I’ve seen derail a number of projects, is the automotive industry demands that you need to supply me your product for my five years of production, and then 15 years of spares afterwards. If you go to a cell manufacturer in Britain and say ‘this is the product for us that’s literally just come to market, and we want to qualify it in for 5 years and then you need to sell it to me for another 15 years after that’, they’re saying that they would have to keep this cell in production for 20 years. That’s right. If you go to Toshiba and ask for an OEM 2001 battery for your laptop, I suspect they’ll politely decline to offer you those spares. So, I think there’s some very interesting challenges in meshing very different industries together to bring the solution to the market.

Jim Motavalli

It is definitely an interesting time. Robert let’s ask you these questions. What makes automated battery module and pack assembly and testing solutions so difficult? And why do so many projects fail?

Robert Lane

When you’re a battery designer going about designing the battery for OEM specs, an OEM will ask for many requirements that are important to the OEM, but you really need to think about what it is that the battery needs to be optimized. I think that’s where the biggest problem occurs and as you get into battery design and battery manufacturing, and you learn that, and then there’s a feedback cycle there. That feedback cycle might take two or three times before you understand as a company that it’s important to look at the battery requirements and put those up front. And there is some compromise, of course, but you can’t make amorphous shaped battery modules with every battery module a different shape, with the puzzle being piecing them together; that can create some difficult challenges. So, that’s a big deal. Also, there’s a lot of other important form factor and design choices that need to be made to enable automated assembly. We’re going into this revolution in AI and automation and it’s important that we go through it step-by-step so that we can be successful at it. That will enable us to make these larger modules at scale.

Jim Motavalli

Do you accept the basic premise of the question, which is that a lot of projects fail?

Robert Lane

Yes, I think all projects fail, but it really depends on how you react to the failures that matters most.

Jim Motavalli

Whether you learn from them or not, basically, I guess.

Robert Lane

Yes, whether you learn and whether you can go through that cycle quickly and get ahead of it and change the design appropriately, fast enough. You need your automation line to be very flexible. As your designs will change, they will evolve rapidly, will go through multiple cycles; there’s alpha, beta, C, D phases to production, and you have that chance to loop it. I always see multiple sets, multiple changes within a phase, especially with batteries. One of the reasons is because of the design, you think of all these design requirements, you have all your interconnects laid out, you have your cooling system and all seems perfect, and then you get to the end, to your thermal event testing, and something bad happens and you must do another cycle and go through it all over again. But that’s just the nature of new technologies and especially power electronic technologies with such high energy densities today.

Jim Motavalli

Udo do you want to address this question and the automation question?

Udo Panenka

Yes. I’ll go into a little bit of and possibly connect into what Robert said here about connecting the cells and pieces in a battery. To give you a little bit of an idea of what we’re talking about, all the pieces and cells in many battery packs have possibly something around six and a half thousand cylindrical cells. If you take cylindrical cells, that means 13,000 weld contacts, and if only one of these welds are damaged the range of your vehicle drops by 1.7%. That shows a little bit of importance of process but it also goes more into what Robert said about lacking standards, a lot of variation, or if you combine this challenging process with lacking standards, then you’re getting into quite challenging territory.

Jim, you touched on the aggressive goals in the beginning here. Basically, the race is on and almost every day another CEO comes up and talks about a more aggressive plan and spends more money on electrification and shorter timelines and shorter ban of ICE cars. I think it’s fair to say that this entire industry is still on a real learning curve; it’s different to be in the old powertrain world where you have people that have done this for many decades.

Basically, when you think about that whole learning curve in battery technology, for the OEMs, for their suppliers, for the automation companies, there is still a lot of dynamic there. So, I think that combination, what the teams have said here, that really is what makes it quite challenging to set automation up in a proper way.

Jim Motavalli

Martin, would you like to comment?

Martin Starkey

Yes. Very quickly and to expand on a point Udo said. I think about every day there’s a new entrant. I think with an electric vehicle, compared to maybe a gasoline type car, in some respects it is simpler in terms of the powertrain, certainly, which makes it a lower barrier to entry to bring a new vehicle to market. I think history will look back and judge just what a dramatic effect these new entrants had on the business model. We’ll use Tesla as a great example. I think, had the business model relied on the classic established OEMs, this electrification journey would have been in some respects easier; it would have been much slower, but it would have been easier because it would have been a controlled introduction. They all have similar processes. They all have similar validation and development plans. I think it’s these entrants that have come in, they’re really shaking it up and have said “well, that’s okay, we’ll just skip steps and we’ll go straight from alpha to gamma and shortcut some of the validation work and get a product out there that will leapfrog our competition.” They’re entirely entitled to do that, but I think it really has stirred up and created this additional challenge on the market to bring these projects to realization.

Jim Motavalli

Well, obviously the automakers have had to admit they didn’t know a whole lot about batteries. And that meant they had to create a whole lot of partnerships with companies and some of those companies don’t work the same way the OEMs do. There have been culture clashes that way.

Let me ask you Martin: what needs to change to make sure that we don’t fall off this mythical cliff with OEMs and their suppliers to build better batteries? What needs to change to ensure that all the needed technology is there?

Martin Starkey

I should probably caveat my own answer with the fact that I consider myself one of those tier-ones that once worked with the OEMs, so that that may skew what I’m about to say, Jim, but I think you need to approach this differently to the classic OEM sourcing; this isn’t going to be answered effectively, necessarily through a well-structured RFQ. This is about partnerships, communication, longer term planning, because you need the tier ones to bring flexibility, because you’re going to introduce flexibility back to Udo’s and Robert’s point through the development of the battery. The new technology is going to come in at the 11th hour in new chemistry in new cell, you’re going to want to grow and jump on that. And what you don’t want is a supplier at that point that will say, ‘Well, let me look at my contract’ and ‘I can PVR your project on this.’ You want far more collaborative and partnership driven solutions, at least for the next 10 – 20 years, because you’re going to need your suppliers to help you out. So, I think that is the most important bit in the short to medium term. Don’t treat it as a classic sourcing exercise because this is something very different.

Jim Motavalli

I was thinking of an example of this kind of cultural clash, when the automakers introduced Apple CarPlay. They tried to have a very fixed schedule for when it would be available and they made many announcements. Because Apple was not on the same schedule, it ended up being introduced years after they first talked about it and their cultures didn’t work the same way. Udo do you want to get in on this question? I think you have an opinion here.

Udo Panenka

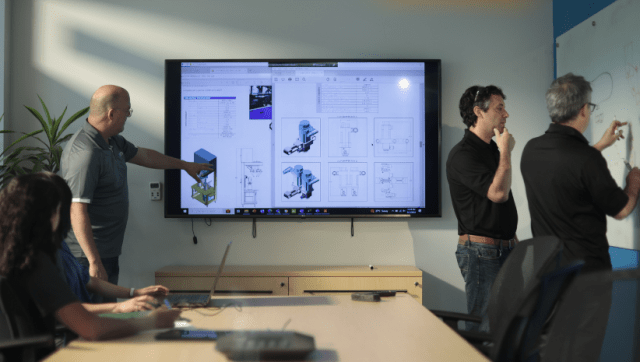

Absolutely. And I think what Martin said is pretty much what we see here as well. I think this is about choosing the right partner if you want to manage this whole thing; there is no doubt about this. I also think there are some important ‘watch-outs’ here. I think the key part is you need to change the way you’re working together with your partner.

What is always to me impressive is if I take a typical battery assembly line, on that line every year you’re producing batteries that have a value of roughly $1 billion United States dollars. And then somebody starts hammering you on $2 million or $5 million on the purchasing price. This is not where the whole thing is, this might be the most expensive saving of your life. I think that the trick is how do you work together with this partner to save 3 or 5 or 10% of your total battery costs? Because that saves you 30, 50 or 100 million US dollars a year. So, with this you need to have a totally different way, and we have made great experiences when our people are actually almost embedded in the customer design teams, so that we understand what changes are on the horizon when it comes to your batteries. We ask: how can we design a line for flexibility? How can we produce the parts later in a good way? How do we bring things like design for manufacturing into your design process? I think that really is a super important aspect; it’s a different way of cooperation. An RFQ will not fix this, so you need to partner, to be embedded, to be involved. Otherwise, you’re going to lose a lot of money.

I think the last thing is you need to choose your partner now. The industry is heating up, suppliers are getting very busy. There will be a time when you might struggle to find enough capacity to get all your production equipment. So, selecting the right strategic partners that help you on a journey, that are committed and can get the job done on time, becomes increasingly important to you.

Jim Motavalli

And, probably ensuring that they actually have the capacity they say they have, that’s going be very important. Robert, do you want to weigh in on this?

Robert Lane

Definitely. I’m right in the middle of it. I think it’s super important to choose a supplier partner that is as technologically advanced as you are but also stable, which is quite difficult to find these days. So, you want a process line that is very agile and flexible, and therefore you want your partners to be able to have an agile, flexible line. For example, making interconnects, a lot of tooling can be involved potentially, so with your design you choose this tooling and sometimes these tools cost half a million dollars and often even more for one single design. But that design will for sure have some changes, and so you’ll have tool mods. So it’s super important that you choose a supplier that is more flexible, that can usher you into production without just throwing in a bunch of tooling and making you make decisions in the beginning and then you’re in a tough spot when you have to change something, because for sure you’re going to change something.

I think that was my approach and I think that should be the approach for all integrators, is how to supply more capability and how to work with your customer to help them. This makes it super important to understand the customer’s intent for the price point, the non-sell costs, as well as what they’re trying to get into their design. The goal is to level the playing field, play on the same winning team and win this thing. It’s certainly a difficult challenge.

Martin Starkey

Jim, you made a very interesting point that I’d like to pick up. You said about making sure you pick the supplier that has the capacity. I think that’s the real rub and where Udo started. To be clear there isn’t the capacity; there are not millions of factories out there.

Part of the problem I see every day is that you’ve got the OEM saying, ‘well, we might source our business with you.’ The company replies ‘Great. Let me know when you’re sure you’re going to source it with me. Then I will spend $20 million, $100 million, whatever, putting the capacity in and oh, by the way, I can’t put it in until you make that commitment.’ You have a little bit of this chicken and egg.

Jim Motavalli

Totally chicken and egg.

Martin Starkey

It goes back to that partnership where I’m going to commit to you that we’re going to work together to bring this to reality. In return, you’re going to commit to start putting flexible capacity in that’s going to join us on that journey. We’ve got to somehow break this vicious cycle that we’re in because the capacity is not there.

Udo Panenka

If you look at this, Martin, and thanks for bringing this up, in the next two and a half years we will somehow need to build everything between 150 and 250 battery assembly lines; many of these lines can take up to 200,000 square feet on your factory floor and sit there for 40 weeks. This capacity isn’t there if we attack it in the way we have so far. We need to really change the game or there will be no chance that we will be able to support production of 12 million electric cars in 2025.

Jim Motavalli

And more in 2030, and it just keeps going up steeply.

I have some questions that I think may have short answers. One of them is: where is battery technology going? I wanted to reference a report that came out yesterday from IDTechEx in England that says we’re looking at 600-mile electric cars by 2025. I thought maybe you could give a one word answer as to whether that’s realistic; I mean there’s a question of whether they would be in cars or they might be on the drawing board. On the drawing board I’m sure but in cars that customers can buy by 2025? Udo, what do you think?

Udo Panenka

Wait, and if so, then we start producing the same assembly lines repeatedly.

Jim Motavalli

Robert, what do you think? 600 miles feasible by 2025? It’s not far from now.

Robert Lane

I’ll take you back on Udo. I think yes, it’s heavily reliant on the new energy density cells and increasing energy density with the exotic technologies like solid-states and silicon anodes, but those types of technologies have significant hurdles because you’re basically starting to nano engineer the active materials.

Jim Motavalli

Maybe we have to ask the basic question: do we need 600-mile electric cars? That is more range than most gas cars have, though some hybrid cars have that kind of range. It means we must put very big, heavy and expensive batteries in cars and so maybe we don’t need 600 miles.

Robert Lane

You always need more batteries.

Jim Motavalli

Martin, what do you think? 600 miles?

Martin Starkey

I think back to my earlier point about the very mature industry that automotive generally is. If there’s a 600-mile battery that no consumer can buy in 2025, I would question why they put the announcement out yesterday; the announcement should have been a year ago, because if that battery is going into production 2025 it has been for some time being developed and designed, and as Robert said, A sample B samples. I say in a development mule, quite possibly, in a car you can go and buy, I’d be surprised. I like being surprised so I won’t discount it.

Robert Lane

Yes. You would need a huge skateboard and you’d have to fill every single spot up with the highest energy dense cell and then still pass the safety testing.

Jim Motavalli

The Lucid company says that the highest iteration of its Lucid Air will have 517-mile range, and that’s supposed to be ready for sale. But Lucid hasn’t had anyone drive its cars yet so we’ll have to see if that car really does in the real world get to that kind of range. That range is very impressive, but it isn’t proven yet.

We got this in the Q&A, and please send questions if you have them via the Q&A button on the bottom of your screen.

Let me ask: Will we have the electric generation capacity to charge up all these cars again? Our subject is really batteries, so we don’t have to go into that heavily. But again, I need a very short answer. Robert, you’re on the screen, so can you answer that?

Robert Lane

Certainly. I think I was surprised to see the Tesla supercharging network come up so fast. Yes, a supercharger can come up faster than a car design. I think there are many companies working on this problem, and it’s being subsidized now; I think it’s a big thing that needs to occur. I think that the great thing about charging is that it can happen anywhere and it’s more flexible than going to the gas station. You can charge at your office, you can charge at your home, you can charge many different locations, and charging technologies are improving all the time. Right now, they’re connector based, and one day there’ll be wireless charging; that’ll be a great day, that I saw it. Yes, I do think that, but I don’t think that will be the short end of the stick. I think a lot of it will be related to the battery cell itself.

Jim Motavalli

Udo, the electric utilities are quite confident that they can handle this addition to the grid. Do you think they can? Will they be able to meet the challenge?

Udo Panenka

I don’t know if I’m the right one who is positioned to answer this question. What I’m seeing is, and I think this is the one of the key drivers to make electric cars very meaningful, there is more focus on getting the energy from renewables.

With renewables the power supply has not been built to store energy. What we’re now seeing evolving, that’s competing a little bit, we’re now seeing a number of companies coming up in the grid battery space. The interesting thing is we have not only a dramatic demand around eMobility that consumes a heck of a lot of batteries but we also have other fields growing like grid batteries to support power supply and more that take up resources, and all these need these batteries. That is not making life easier but even a little bit more challenging.

Jim Motavalli

Let me ask another question from our Q&A viewers. They want to know about solid-state batteries, and there’s been a lot of talk about them. A lot of the development is still on the computer screen, it’s theoretical. We don’t actually even have any solid-state packs that are automotive grade that I’ve ever heard of, but we’re getting these bold predictions from some of these startup solid-state companies about what they’re going to be able to deliver and soon.

Udo do you think this could be realized? Are you seeing solid-state moving quickly so that solid-state will be in cars anytime soon?

Udo Panenka

I would say optimistic predictions say possibly 2025, and we get involved in some conversations around how would battery solutions look like for solid-state, and at the moment more on the process evaluation phase, on the early pilot evaluation phase. So, there is some dynamic and there are more people putting more money into it and this could definitely lead to extremely interesting breakthroughs as they are changing quite a lot of aspects, including a big driver being the weight of the battery.

Jim Motavalli

Safety too, right? It’s supposed to be safer. If not, battery fires would be a thing of the past.

Udo Panenka

Absolutely. I think that’s another ‘watch out.’ We don’t want to start building in 2025-2026, from scratch the whole production capacity for the 12 million batteries we have in place by then. We need to build these assembly lines now, with a view to try to answer how on Earth will we be able to flexibly adjust so that if a technology change comes, we’re able to build on what’s already installed?

Jim Motavalli

Interesting, Martin, do you want to address this? Are you looking at solid-state?

Martin Starkey

Indirectly. The interesting thing for us, Jim, is historically our markets are always niche. Whether it’s aerospace, defense or automotive, it means we’re typically the smaller volumes, which means usually we are the high-performance where innovative technology gets cascaded through. So, whether it’s sports cars, or eTurbines or potentially going into Vito vehicles and things like that, I think if it does show its face, it will be in these premium applications, lower volume, where they will go through a certain level of validation; I think that kind of business model has worked very effectively over the years in automotive where it’s always the lower volumes, the higher performance, higher price tag vehicles that get the guinea pig technology, if you like, passed through. If it is coming, I’ll be looking to those sectors to see it show its face first.

Jim Motavalli

Robert, I was wondering, when you were at Tesla if Tesla was looking at solid-state batteries, and if you’re looking at it in your own company?

Robert Lane

I’m not sure how much I can say about that, but I think for sure every company is looking for all the different cell types, and they’re all aware of all the different cell types. But when it comes to scaling you go to the main guys that have the capacity and the lines and the ability to make good quality product.

I think that I see many companies entering into the market right now and those companies doing that are producing saleable product and are very focused on cost, the cost story and the reliability and quality of those batteries, as well as the energy density. This means that they’re looking at what is important today and whether that can evolve into something else. I think the current technologies can certainly evolve as the anodes become more exotic and you’re able to reduce costs. I think back at a stable path towards this and there’s the mythical goal of solid-state that everybody always wants, but they have significant challenges. And it is not just cycling once but thousands of times and not having dendritic formations that penetrate and short the cell. These are challenging problems, and the reason why your energy density does increase over time.

But even if you solve one of these problems it still takes time, as Martin said, to make sure there’s no other issues with them; that’s why it is important to stabilize as we head into this new market. When new technologies happen, we must have a place where they can go to be developed and evolved quickly and correctly; the premium markets are a great market for that.

Tesla started out with the Roadster as a premium product that could do many awesome things and that’s why people bought the car; it wasn’t just because it was an EV. It’s not like a golf cart. That ushered in the Model S and then to the Model 3, into this next model II car. There’s that evolution that needs to occur.

Jim Motavalli

Udo we look at the question of these battery lines, getting back to the central question we’re talking about today. Is there anything the automakers and their suppliers can do to future-proof their lines so we don’t have some of the problems you’re talking about?

Udo Panenka

I personally don’t believe that there will be a large level of standardization in the industry, which would make life easier. I think there might be a kind of modularization of products that car makers will use for the different type of cars they’re using; there is a huge opportunity.

I’m coming back to that piece on the one side of including your automation partner in your design activity to drive design for manufacturing design for flexibility, and the other piece is really trusting your automation partner on their spec. I think automation partners that have done a number of challenging projects know what good way laser welding looks like, they know how you can overcome tolerances in yourselves that in certain applications don’t work, they also realize that you’re moving your specification from a powertrain application over to battery. I see OEMs that are measuring 700 data points on a battery assembly line and get no insight on how they can improve uptime, availability and all such things. So, I think that close cooperation, partnerships, strategic cooperation, involvement, and trust that somebody who has proven that they can execute such projects successfully, that sometimes they know a little bit better what good looks like. I think that type of cooperation and close partnership is what can help in the current environment.

Jim Motavalli

We only have a couple minutes left and several people have asked about swappable batteries. That’s been tried not very successfully by companies like Better Place in Israel, but it keeps coming up. Maybe you could just give very quick answers of a few of words. Swappable batteries: are we going to see those? I don’t personally see it happening, but what do you think? Robert?

Robert Lane

Yes, I think this is something that’s very interesting that many companies try to approach; I’ve seen it at Tesla too. The problem is your connector must be very robust and handle all the cycles; that’s a significant challenge and I think it’s an unnecessary challenge. I don’t really believe in swappable batteries at this point.

Jim Motavalli

Martin, what do you think about swappable batteries?

Martin Starkey

Yes, I won’t go into all the reasons why I don’t think, but I think there’s a whole range of reasons that they’re probably not the answer. I think that you see the innovation in charging times and if you plot the graph it won’t be long before the charges will charge faster than you swap the batteries. I’m with Robert on this one.

Jim Motavalli

Brenda, I see you popping up. Does this mean we’re out of time?

Brenda Staines

Yes. Maybe Udo wants to give his last comment on that?

Udo Panenka

I think everything has been said. In my opinion, mainstream swappable will not happen, but will for niche applications; Nio is great on that. But that’s about it.

Brenda Staines

Ok, thank you very much. Thank you everybody for joining us today, it was a fantastic conversation. We had loads of questions and I hope you enjoyed this discussion today. Enjoy the rest of your day or evening and see you next time for more Reuters events.

Jim Motavalli

It was very stimulating. I learned a lot from your panelists. Thank you, Martin. Thank you, Udo. Thank you, Robert.

Udo Panenka

Yes thank you.

Martin Starkey

Jim and Brenda. Thank you.

Robert Lane

Thank you, Brenda.

Brenda Staines

Thank you everyone. Okay. Bye.

Jedes Projekt ist einzigartig. Wir möchten uns Ihre Herausforderungen anhören und Ihnen mitteilen, wie Sie Ihr Projekt durch Automatisierung rechtzeitig auf den Weg bringen können.